“Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” Lyrics (by The Platters from Hearts in Atlantis Soundtrack)

They said someday you’ll find

All who love are blind

Oh, when your heart’s on fire

You must realize

Smoke gets in your eyes…

Now laughing friends deride

Tears I can not hide

Oh, so I smile and say

When a lovely flame dies

Smoke gets in your eyes

Smoke gets in your eyes

Chapter 1

A March 1999 Vogue article, “Up In Smoke,” came to hand in 2001. Sidney Urquhart, daughter of dramatist Sidney Howard, wrote a memoir of most everyone she knew, all consumed, literally, by smoking tobacco. Reading this moved me to put down an account of my own saga of temptations and falls from grace with nicotine.

I think I am 13 years old. I am smoking a pipe full of Sir Walter Raleigh tobacco. I’m in a large, discarded shipping crate that I had converted into my boyhood play fort. It is situated not far from home in the empty lot of an aunt and uncle who would one day build their home there.

I don’t recall the steps I took to acquire the pipe or how I purchased the tobacco (or the shipping crate for that matter), but get them I did. Were legal restrictions and social norms of those times that lax? Of course, no adults in my family would have condoned my habit. If I was chided or forbidden to smoke, no change in my habit ever came of it.

Was my child’s play fort a subliminal investigation of smoky caves of ancient times? Was it a subconscious purpose, a sanctuary, earth-womb, a reenactment of the dim grottos of prehistory? What is it about the psyche—even that of a child—that wants to descend into the dark places?

The shipping crate was my getaway and meeting place with my friends. I don’t recall sharing the pipe with the other kids—maybe a little. The smoking was my private claim of independence, a ritual drama of faux maturity.

I stowed my pipes and pipe cleaners in a box under a secret flap in the dirt floor of the fort.

Some years later, someone told me the story of his first experiment with smoking. He and some friends took some cigarettes from his father’s pack. They ran off to the woods in the neighborhood and lit up. Choking and coughing, one of the boys threw a stick into the trees and hit a nest of ground bees. The bees swarmed around the boys, and they associated this harsh backfire from nature with the forbidden cigarettes.

I did not have such a negative conversion moment, but I wonder that I kept smoking through all the mess of the pipe cleaning process. Even at an early age, the human Spirit is enticed by the strange, grossness of the material world—shades of things to come. It’s a trade-off at any time in life. For the mood altering effects of nicotine, the headiness of being “bad,” I endured the hot smoke drawn into my lungs and the terrible taste on tongue and in saliva.

That empty lot where I had erected my fort—that was the land site that my maternal aunt Rose and her husband Bill owned. Until they started building their home, I would be lord of this realm, and I was casting my lot for my destiny, yet to be played out—a smoker’s life that was to last for decades to come.

Also yet to be played out, years after I had grown up, was Uncle Bill’s fate as a lifelong cigarette smoker—lung cancer. As the dangers of smoking became more evident socially, the warnings began to be printed on the pack. Bill joked as he read the warning to me: “Smoking cigarettes is dangerous to your health, Art.” He would comment ironically: “It says your health, not mine.”

Another aunt and uncle were smokers. Aunt Lucy smoked throughout my childhood, but quit when she retired and she lived to be eighty seven. Uncle John had been a smoker in his youth and years as a World War II soldier. When he returned to the States, one day he just quit smoking. As he told it, he threw away a pack of cigarettes and never went back on his decision. Probably the rigors of withdrawing from nicotine were nothing compared to his bravery in the war. Also, he was of stoic Scotch heritage (surname Dickey). He lived to his ninety first year.

I never saw my father smoke, but he told of experimenting as a child. He thought up a clever play act. He had access to a store room where he would smoke in the second story above his father’s shop on a busy downtown street. He told of putting a plank on two boxes, then stepping up and walking back and forth in front of the shadeless windows in order to appear tall, as he smoked.

My mother was not a smoker, though she might have had a cigarette on New Year’s Eve with Aunt Lucy.

Another uncle, Joe, died of lung cancer. He smoked throughout all the years I knew him, and nicotine only added to the taxing industrial work that he did.

Chapter 2

In my mid-teen years I got my first grownup job as cashier in a drug store. The most grownup products I sold (and I don’t mean condoms, which were purveyed from the pharmacy) were tobaccos and smoking paraphernalia: pipes, Zippo lighters, etc. I was a consumer as well: Chesterfield, Pall Mall, Old Golds, Camels, Lucky Strikes, Phillip Morris, and Piedmonts.

My favorite was Pall Mall, which was pitched to my gullible attention during the broadcast of Friday-night wrestling in prime time. “Pall Mall…famous cigarettes, and they are mild.” My grandfather smoked Italian stogies, and so did I eventually—trying for the tough guy look, even as a high school freshman.

Then a sudden awakening of a neglected heritage flashed across the nation—Marlboro filtered cigarettes. This represented something drastically different from the traditional images of nicotine—the manly, macho, Cowboy persona. I went for it.

At a smoke shop I discovered the Egyptian cigarettes “Helmar,” packaged in a small box with head of Pharaoh embossed on label. Now I felt more sophisticated. Many years later at the Santa Fe Flea Market I found an empty Helmar box amidst a jumble of dusty, worn-out gewgaws.

Speaking of sophisticated, I became acquainted with suave people: the Jacksons—Charlie, his wife and daughter—fellow amateur thespians at the Wilmington Drama League, another venture for me out into the world. Charlie smoked unfiltered cigarettes and carried them in a case. He would draw one out of the case, close it, and then briskly tap, tap, tap it on the case to compact the tobacco. (I put that bit of “stage business” into my character—still only a high school sophomore.) Then he would light up, and the Zippo’s metallic clink would ring through the air, along with cloud of fume and lighter fluid—the dramaturgy of smoking.

Kent (Famous Micronite Filter) dramatized smoking scenes on the back of LOOK magazines—a young couple on a spring afternoon having coffee, apples, cheese—and smoking Kents.

I tortured and punished my young lungs, gums, mouth and teeth all through high school and beyond. The youthful body can take so much abuse without really showing it. And I never gave it a second thought, nor did many other people all those years ago.

Chapter 3

University: By the time I was in college, I was breathing in as many as 30 cigarettes a day, except when I had a bout of flu or cold.

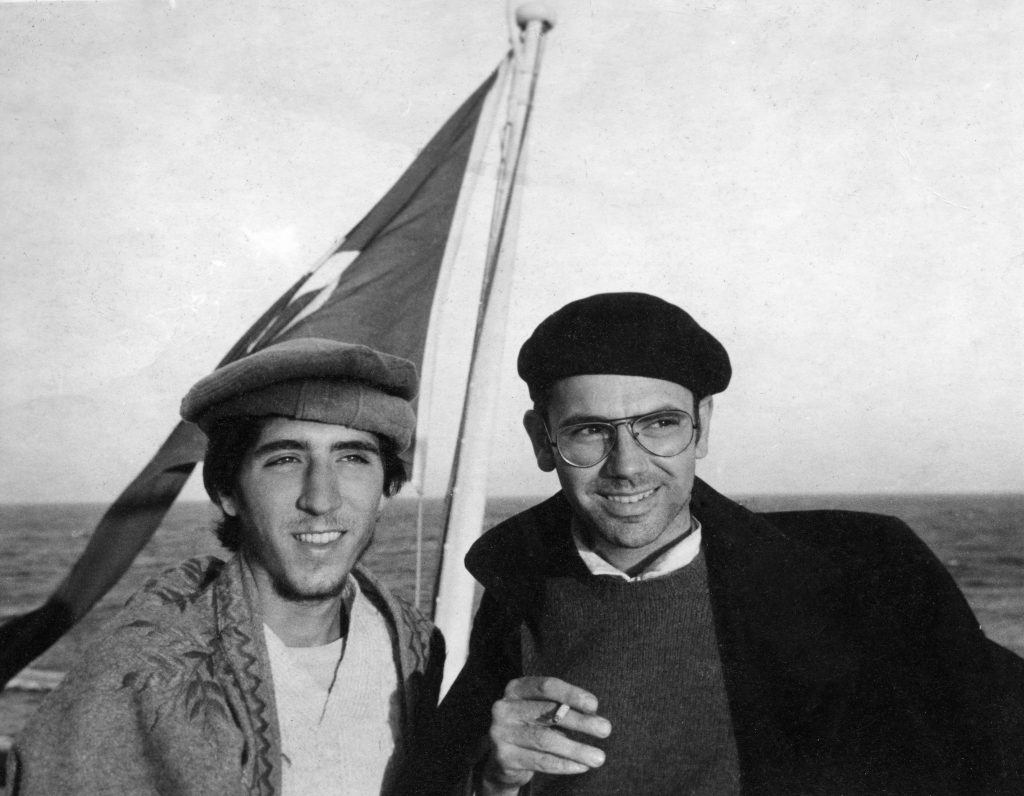

Peace Corps: I applied, and requested Morocco, but I didn’t speak French. They said “How about Afghanistan?” Where is that? WOW! Okay. Yes, fly me to Chicago and I’ll interview. I got recruited and was lucky to be assigned to in-country training and teaching English in various institutions. This venture beyond the US would bring me into a world of peoples, sights, land, camels, donkeys, sheep and goats, a land dramatically different from anything I had ever seen. I was going to be living in Afghanistan, officially then the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan—a landlocked country forming part of South, Central and to some extent Western Asia. The world of smoke would be exotic too—and I’ve got a collection of empty cigarette packs to prove it.

In Kabul I smoked a Russian brand, and the famous Gauloises of France. From Pakistan came a brand, K-2, named for the highest mountain in that land—possibly the worst cigarette ever conceived and manufactured in the world. These I smoked regularly and mindlessly, cluelessly to the point of getting a severe case of bronchitis which was aggravated by the dry, dusty desert atmosphere—more dry and dusty than New Mexico because Afghanistan is a land of rocks, arid mountains and sand. I coughed so vehemently that my torso muscles were sore until I quit torturing myself. (By the way, that jagged, open landscape rushed back into my mind when I first arrived in New Mexico, enough for me to set down roots here.)

An R&R vacation brought me to Thailand, where I found the mildest cigarettes I have ever smoked—also a light, soft whiskey of the Thai people, and I mused that, of course such mellow pleasures would be there, in a Buddhist land.

Having completed my commitment to the Peace Corps, I traveled southeast by bus through the Khyber Pass, Pakistan and to India. The cigarette packs in India and Pakistan still carried the shades of the British Raj. The size of these cigarettes was smaller by US standards, and only 10 to a pack. The names were poetic, impressive and spoke of the arcane dominion perpetrated by the British Empire: Cavander’s Navy Cut, Marcovitch/Red & White, Marcovitch/Blue & White, Scissors Cigarettes, Special Army Quality manufactured by W.D. & H.O. Wills, Bristol & London (Inscribed with Hight Award, Brussels 1897), Wild Woodbine, Virginia Cigarettes (Grand Diploma of Honor, Antwerp International Exhibition 1885).

Eventually came my travels back homeward by train, bus and taxi overland, again through Pakistan and Afghanistan, and then on to Iran. The nicotine products there had a special charm—unfiltered, very thin and short, 100 to the little box. Thereafter would be brands of Turkey, Greece, Italy and Luxembourg, from which I departed by airplane back to the life which was to come for me.

Chapter 4

Recovery—Many years hence here in New Mexico I undertook to study therapy and psychology at Southwestern College, Santa Fe. One of our courses entailed examination of the concept and practice of “service”—service to self, in relationships and to community. In service to myself, I committed to quit smoking finally, once and for all, after years of false starts and stops. I finally did clean up and broke the hold nicotine had on me. It was 1993.

One of the major recovery tools that worked for me was to repeat and repeat and repeat silently to myself: “I want the best for myself and I am not going to settle for anything less.” The recovery started with commitment, then repeating and refining my motives, and at last a system of behavioral and cognitive improvements throughout the week. There have been some relapses now and again since then, but no prolonged slides downward to habitual smoke.

Part of the study of psychology found me looking back through my life. I had lived through decades of smoking. The improbable glamour, the theater ritual of the lighting-up, the faux sheik, dude, beau geste façade of it all—and my earlier years of derring-do had long since passed.

One of the brands in India was called Passing Show, Tipped Virginia. What an apt name for the foolish business of smoking nicotine—a show indeed, and a passing show at that—though with deadly results with which we have all become too familiar.

§

FINIS

Originally published January 10, 2013 at: https://santafe.com/blogs/read/smoke-gets-your-third-eye